Join the movement at Inman Connect Las Vegas, July 30 – August 1! Seize the moment to take charge of the next era in real estate. Through immersive experiences, innovative formats, and an unparalleled lineup of speakers, this gathering becomes more than a conference — it becomes a collaborative force shaping the future of our industry. Secure your tickets now!

More than five years after the filing of the first bombshell commission case, the Council of Multiple Listing Services has weighed in, coming out swinging against the U.S. Department of Justice’s proposal to decouple commissions.

On Wednesday, March 27, CMLS, a trade association made up of more than 225 MLSs in North America, asked the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts to accept an amicus brief telling the court to disregard a statement of interest the DOJ filed on Feb. 15 in a major antitrust commission case known as Nosalek.

On the same day, attorneys for CMLS member Northwest MLS (MLS) similarly asked the court to accept their own separate amicus brief detailing alleged flaws in the DOJ’s filing. NWMLS’s new president and CEO Justin Haag, formerly the MLS’s general counsel, began serving on the CMLS board of directors in January. CMLS’s MLS members have more than 1.7 million agent, broker and appraiser subscribers combined. NWMLS, which is broker-owned and not Realtor-affiliated, has more than 33,000 subscribers.

“The Council of Multiple Listing Services (CMLS) takes the extraordinary step of filing an amicus curiae brief before this Court to oppose this effort of the Antitrust Division (DOJ) to impose a policy preference on the U.S. residential real estate market that lacks empirical support, conflicts with principles of the Sherman Act, and has negative practical implications for consumers which DOJ has not taken into account,” CMLS’s amicus brief reads.

In its statement of interest, the DOJ rejected rule changes in a proposed settlement between homeseller plaintiffs and defendant MLS PIN (a CMLS member) and instead called for “an injunction that would prohibit sellers from making commission offers to buyer brokers at all,” which the agency said would promote competition and innovation between buyer-brokers because buyers would be empowered to negotiate directly with their own brokers.

In the filing, the antitrust enforcer pointed to rule changes Northwest MLS made in October 2019 (making the offering of buyer broker commissions optional) and October 2022 (specifying that buyer broker commissions, when offered, will come from sellers rather than listing brokers and further laying out sellers’ options regarding compensation) that are similar to those in the proposed Nosalek settlement, but that the DOJ said appear to not have had a meaningful effect.

The agency said the changes didn’t lead to a decrease in buyer broker commissions, “had no apparent effect on either the portion of listings for which a buyer-broker commission offer was made or in the number of offers with zero compensation,” and did not lead to a decline in buyer broker commissions in large metro areas in NWMLS’s region relative to such commissions in other large metro areas where there were no similar changes to MLS rules.

At NWMLS, between October 2019 and March 2022, 99.2 percent of NWMLS listings continued to offer a buyer broker commission (flat from 99.3 percent before the rule was eliminated). Virtually all, 94.5 percent, offered a cooperative commission above 2 percent.

According to CMLS, the court shouldn’t consider the DOJ’s arguments because of “critical flaws.” The trade group’s filing contends that “the internal DOJ study [of the NWMLS changes] suffers from conceptual and methodological problems and does not provide sufficient information for the Court to evaluate its claims,” including only using transaction data from only one brokerage in NWMLS’s footprint for its analysis.

“It is missing, for example, any data about average prices or commissions; who the single real estate broker was that it used for analysis; how representative that broker’s experiences are of brokerage firms generally; which thirty-one other markets DOJ analyzed; or how many transactions were analyzed in any market at any time,” CMLS’s amicus brief states.

The trade group also faulted the DOJ’s comparison of NWMLS to other markets without controlling for differences in those markets, which CMLS said meant the DOJ’s analysis couldn’t actually determine the effect of any NWMLS rule changes.

“In short, the SOI purports to provide empirical evidence to support its claims, but the Court should credit none of it; all of it is either not empirical evidence at all, chronologically or geographically inapposite, or methodologically flawed,” the CMLS filing says.

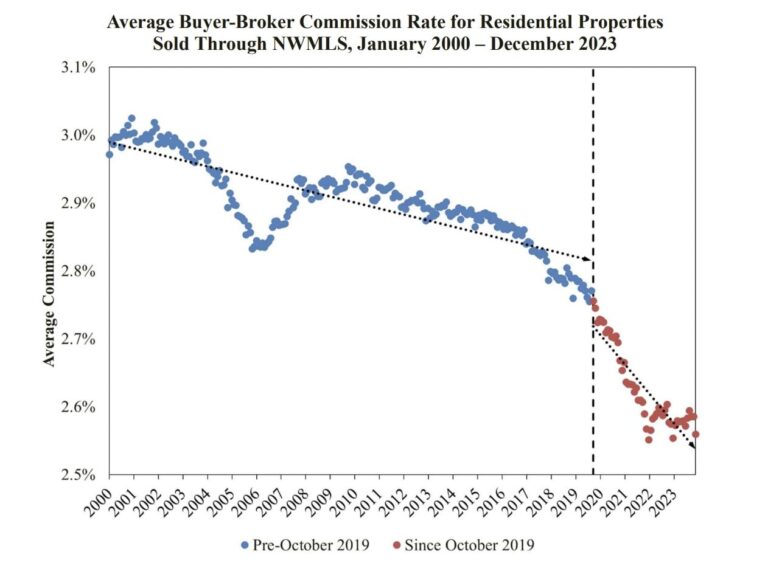

Moreover, CMLS said its own data analysis by economists John H. Johnson IV and Michael Kheyfets showed “probable positive effects of the rule changes” in the proposed Nosalek settlement, including lower commissions. The analysis looked at all 1.8 million listings from NWMLS in Washington and Oregon sold since 2000, according to the filing.

“[The analysis] demonstrates that cooperative compensation offers have been declining in NWMLS since 2000, but they have declined markedly faster since the NWMLS 2019 Rule Change,” the filing said.

“‘Buyer-broker compensation rates through NWMLS were declining at an average of 0.4% per year from 2000 to 2019. After the 2019 rule change, the decline increased to an average of 1.5% per year.’”

Screenshot from CMLS amicus brief in Nosalek

Put another way, the NWMLS 2019 rule change led to a decline in commission offers of 0.118%, so buyer brokers were offered 2.382% instead of 2.500%, and the NWMLS 2022 rule change led to a further decline of 0.021%, according to the filing.

“These declines are on top of the declines in rates that were already in progress,” the filing says. “The data thus support a reasonable estimate that the buyer’s broker received an average reduction in commission on the sale of a $750,000 home (the average sale price in NWMLS) of more than $1,000 (e.g., $17,708 instead of $18,750) as a result of the NWMLS rule changes.”

“Given the average home price in MLS PIN today is in the same range as those in NWMLS, consumers buying through MLS PIN under the Proposed Settlement Policies are likely to experience similar savings,” the filing adds.

CMLS also maintained that the DOJ’s suggested ban on sellers offering compensation to buyer brokers at all would itself violate antitrust laws.

“Such a rule, if an MLS adopted it, would violate the competition-enhancing principles of the Sherman Act, because it would mean that competitors—brokers who participate and operate the MLS—would be agreeing to dictate that competing seller brokers cannot engage in lawful marketing of property,” the filing says.

In addition, CMLS criticizes the DOJ’s assumption that the transition to its suggested policy change would be smooth.

“[The SOI offers no evidence that DOJ has sought input from third-party industry participants, including mortgage banker associations; appraiser associations; the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which purchase pools of conforming mortgages from lenders; the Federal Housing Administration (FHA); and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA),” CMLS’s filing says.

“Meanwhile, the Proposed Settlement Policies mirror provisions in effect in Washington state for nearly five years without reports of negative consequences. This Court should prefer the proven track record of the Proposed Settlement Policies to the

optimistic imaginaries of DOJ’s policy preference.”

CMLS stresses that the DOJ doesn’t appear to have considered the effect of its policy preference on first-time homebuyers, low-income buyers, and minorities.

“Importantly, DOJ assumes that the seller will pay the buyer’s broker as part of the negotiated deal,” CMLS’s filing says.

“DOJ offers no evidence for why that will be the case, and other scenarios are possible, and perhaps likely. For example, if a seller receives two offers that are equally financially satisfactory, one where the seller must pay the buyer’s broker and one where the seller need not, a seller might choose to go with the ‘cleaner’ or ‘simpler’ offer, just as sellers today may prefer a cash offer to one that is contingent on financing.”

The CMLS filing concludes by indicating that the DOJ had overstepped its bounds.

“DOJ seeks to secure a major change in U.S. residential housing policy by commenting on a proposed antitrust settlement among private parties, instead of by an enforcement action of its own or by encouraging rulemaking by a federal agency empowered by statute to do so,” the filing says.

“The Court should decline to credit the SOI’s arguments, given that DOJ lacks robust empirical evidence to support its policy preference, overlooks the anticompetitive nature of its policy preference, and does not have the institutional expertise to assess the effects of its policy preference on the real estate market.”

NWMLS’s amicus brief also slams the DOJ’s filing, calling it “ill-informed,” “ill-supported” and “based on a highly flawed analysis of woefully incomplete data” from a single brokerage “over too short a period of time.” The filing contends the DOJ had plenty of NWMLS data at its fingertips that it had demanded from NWMLS that it could have used for its analysis but chose not to.

“Unfortunately, DOJ demands immediate impact from NWMLS’ changes, and then using limited data from a single brokerage firm in a very short time period, DOJ declares NWMLS’s changes to be ineffective. Evolution takes time,” the filing says, pointing to recent, similar commentary from the Consumer Federation of America regarding changes in the proposed National Association of Realtors commission settlement and from a plaintiffs’ attorney in the bombshell Moehrl commission suit..

The filing also criticizes the DOJ’s “myopia” in only allegedly only considering “decreased buyer broker commissions” the barometer for competition.

“Transparency and the expansion of informed consumer choice are the guiding principles of NWMLS’s revised rules,” NWMLS’s filing says.

“Providing consumers with more information in turn promotes competition and lowers prices. In revising the rules, NWMLS created a more open and free market for consumers of brokerage services.”

NWMLS suggests the DOJ’s proposal will lead to “secret” deals between brokers.

“DOJ’s preferred system, in which there is literally no opportunity for compensation transparency in the MLS, invites brokers to make deals in secret, creating opportunities for deceptive practices, discrimination, and unfair housing,” the filing says.

However, while NWMLS attempts to poke sundry holes in the DOJ’s analysis, unlike CMLS’s filing, NWMLS’s amicus brief contains no data or data analysis to counter the DOJ’s arguments regarding the rule changes’ effects on commissions.

The filing seems to eschew even attempting that sort of inquiry, noting, “NWMLS does not analyze levels of compensation offered by its members, much less the amounts of compensation actually received by buyers’ brokers after negotiations between parties.”

Inman has reached out to NWMLS, CMLS, and the DOJ for comment and will update this story if and when responses are received.