The ownership of approximately 80 works by the Austrian artist Egon Schiele has been the subject of civil lawsuits for the past 20 years. These disputes have pitted the heirs of Franz Fredrich (Fritz) Grünbaum, a Jewish cabaret performer and art collector who died at the Dachau Concentration Camp during World War II, against museums, art institutions and collectors throughout the United States who have been in possession of these works. A debate continues as to what happened to Grünbaum’s art collection following his death—whether his family took possession of the works or whether the Nazis confiscated and later sold them. While this dispute historically has unfolded in the context of civil lawsuits, a New York State criminal court, for the first time since 2017, was the forum in which a title claim to allegedly stolen art was adjudicated.

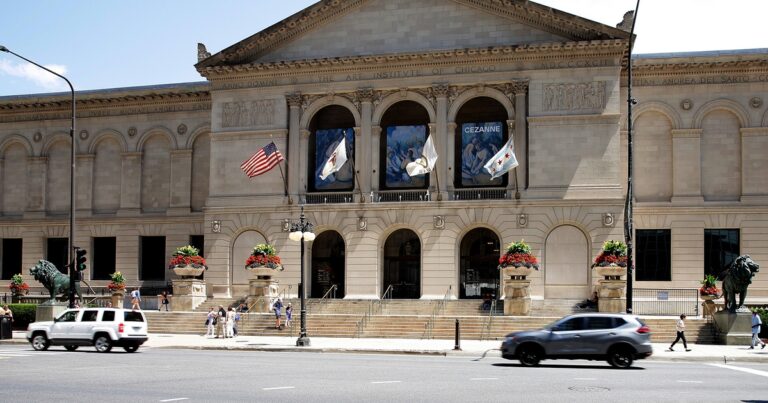

On April 23, 2025, a New York State Supreme Court judge issued a long-awaited decision in the matter of the seizure by the New York County District Attorney’s Office Antiquities Trafficking Unit of Schiele’s 1916 drawing titled Russian War Prisoner currently in the possession of the Art Institute of Chicago. While the DA’s office sought to restitute the drawing to the Grünbaum heirs, the Art Institute, to the contrary, argued that it’s the legal owner of Russian War Prisoner, as it had purchased the drawing in 1966 based on evidence detailing the work’s legal sale by Grünbaum’s sister-in-law to a New York art dealer in the 1950s. The Court granted the DA’s application and ordered that the drawing be turned over to Grünbaum’s heirs. In so doing, the court made some important findings that will impact the wider art market beyond the specific facts of this case.

Stolen Property

As a threshold matter, the Court ruled that Russian War Prisoner constitutes stolen property under New York’s Penal Law (in March 2024, however, a federal district court in Manhattan dismissed a civil case that the heirs had brought against the Art Institute, holding that the heirs failed to prove that the work had been stolen). The Court found that the Art Institute’s reliance on a one-paragraph facsimile transmission from the New York art dealer who vouched for the work’s provenance but who was later unmasked as a dealer in Nazi-looted art at the time the Art Institute was in possession of the work fell short of the Art Institute’s own and market-wide standards of due diligence. The Court particularly faulted the Art Institute for having failed to make reasonable inquiry into the provenance of Russian War Prisoner after having learned of the dealer’s connection to the Nazis, notwithstanding the Art Institute’s assertion that Grünbaum’s sister-in-law was able to recover his art collection from his storage unit after the war. The Court’s finding underscores the duty of ongoing due diligence specifically imposed on museums and art institutions regarding works from this wartime period. However, in this new legal landscape, it would also be prudent for collectors to increase their due diligence on art transactions.

New York Court’s Jurisdiction

Although the Art Institute has been in possession of Russian War Prisoner since it acquired the drawing in 1966, the Antiquities Trafficking Unit has taken a very broad view of its ability to assert jurisdiction over artwork located outside of New York State. As New York is arguably the largest and most important art hub in the United States, the Antiquities Trafficking Unit’s position has been that any work that has passed through New York at any time and for any duration is subject to a New York court’s jurisdiction. In the case of Russian War Prisoner, the work was imported from Europe into New York, where it was housed and openly displayed for a time prior to its purchase by the Art Institute in 1966. The Court agreed with the Antiquities Trafficking Unit’s broad assertion of jurisdiction, confirming the DA’s ability to bring actions against artwork that was once but is no longer located in New York. The Court’s finding underscores that in this new legal landscape, it would be prudent to be mindful of whether an artwork has entered into New York, and if not, whether an owner would want to permit an artwork with provenance gaps to enter into New York in the future.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the Court’s decision is that it was issued in a criminal court in the first place. Historically, when there have been two or more competing claimants each asserting title to a work of art, the matter has been adjudicated in a civil, not criminal, court. Although law enforcement has always been able to seize property pursuant to a search warrant and seizure order based on probable cause of theft, the property would be released to whomever prevailed in the civil action. Now, however, this Court has ruled that a certain provision of New York’s Penal Law—what the DA’s Office has characterized as a “turnover proceeding”—is an appropriate vehicle to adjudicate civil restitution disputes in a criminal forum even in the absence of a pending criminal prosecution of a defendant who has been charged with a crime. All that’s needed now to invoke the jurisdiction of a criminal court is an active grand jury investigation, whether any charges are eventually filed. Unlike civil title claims, which have a statute of limitations and a potential laches defense, there’s no laches defense for a criminal title claim, and the statute of limitations for a title claim in the context of a criminal investigation never expires if the party against whom the claim is being asserted is in actual or constructive possession of the artwork. Practically speaking, this means that now the risk of an art title claim isn’t guaranteed to lessen over time or with more public exposure.

Appeal Pending

The Art Institute has appealed the Court’s decision. On May 6, 2025, an appellate court issued an emergency stay pending appeal, pausing the return of Russian War Prisoner to the Grünbaum heirs. The stay allows the work to remain in the Art Institute’s custody while the case works its way through the appeals process. This appeal will have a significant impact on the market for art with unclear provenance and should be tracked closely.